Southern Food and Graph Theory: Part 2

The first step I'm going to take in analyzing peg solitaire is to model the game as a graph and then examine the properties of that graph to see what techniques would be feasible.

Prerequisites

If you're not familiar with graphs, don't worry! I'll cover the concepts you need to know in this prerequisites section. We wont be needing much mathematical rigor in this project. So, I'm using casual definitions that sacrifice some correctness or precision for efficiency in communicating the core idea.

A graph is a set of nodes and a set connections between them, called edges. For our purposes, edges have a direction, which means they function like a one-way road. If there is a directed edge from node to node , then we say that is adjacent to . Because the edge only goes one way, is not adjacent to . The neighbors of are all other nodes that are adjacent to .

A cycle is a series of hops between adjacent nodes such that you start and end on the same node.

Graph Model

What we want is not only a way to solve the game, but also see how different board states relate to one another. For example, a move you make very early in the game might be irrelevant, or it might decide whether the game is winnable.

Let's imagine creating a node in our graph for every possible state the game board could be in. For some games, literally doing this is impossible, but this version of peg solitaire is small enough that enumerating the whole game is trivial for a computer (I'll put numbers to this later). For the rest of this section, the terms "board" and "node" are equivalent.

These nodes aren't very helpful by themselves. We need to know how they relate together! We need to add edges to our graph.

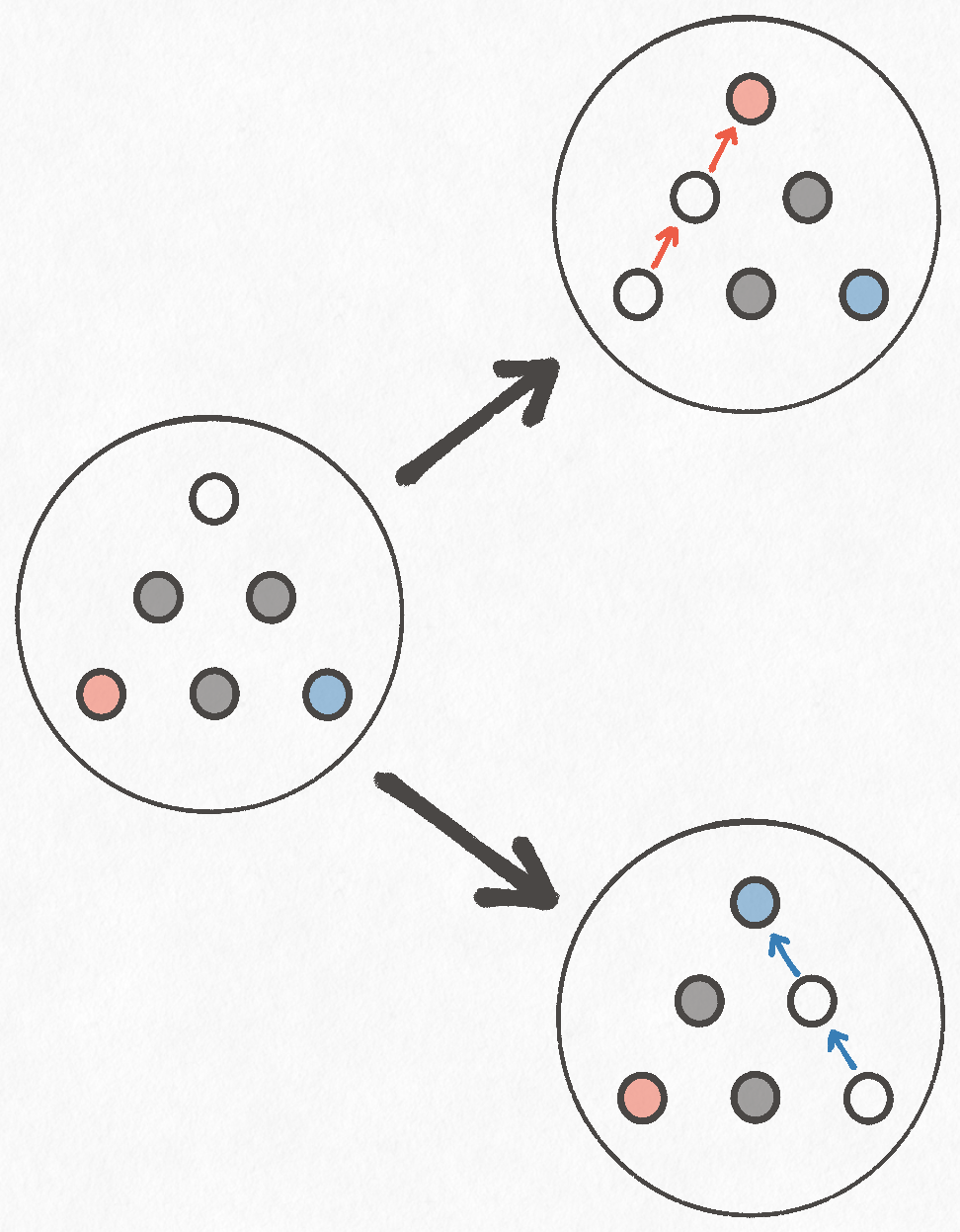

For any possible game board, there are some number of moves (potentially zero) you could make. For each move, you get a new board state that is the result of playing that move. We can use this fact to convert game moves into graph edges.

Given two game boards (nodes) and , we'll add a directed edge from to if there exists some move on the board that results in the board .

Graph Properties

The properties of this graph will inform us about what methods we can use to process it.

The most important observation we can make is that this graph has no cycles. We can prove this using the fact that edges correspond to moves in peg solitaire. Every move takes a peg off the board, and edges in our graph correspond exactly to moves in the game.

In order to have a cycle, you'd need an edge to go from a board with fewer pegs to a board with more pegs. That's clearly impossible based on the rules of the game and how edges are defined in the graph.

Because the graph has no cycles, we don't need to worry about getting stuck in infinite loops while exploring it.

We can also observe that all solutions to the game take the same number of moves. You start the game with 14 pegs, and all winning solutions end with 1 peg. Since each move removes exactly one peg you'll need to make 13 moves no matter what solution you use. For the graph, this means that we don't need to be particularly careful how we traverse the nodes in order to find solutions.

If some solutions were shorter than others, we'd be constrained to using specific traversal techniques in order to guarantee we find the shortest solution.

Graph Size

We should also try to get a sense for the size of the graph. If the graph is too large, we might have to write a special algorithm or change approaches entirely.

The two properties we're interested in are the number of nodes and number of edges.

To compute the number of nodes, we can think of the board as a 15 digit binary number, with each slot on the board corresponding to a unique digit. With that, the number of possible boards is the same as the number of 15 digit binary numbers, or . However, we must account for the fact that the completely full and completely empty boards don't exist in peg solitaire. Thus, the real number of nodes is , or . This number of nodes is trivial for a computer to handle.

Now, exactly counting the number of edges with pure math is beyond my skill-set. However, we can use some observations to perform a rough estimate. Firstly, the number of possible moves on any board is going to be limited by either the number of empty spaces, or by the total number of pegs. This is because you need both a peg to move and an empty slot to jump into. Second, the maximum number of moves that can be associated with any empty space is 4 (you can prove this for yourself by exhaustively checking each slot and its neighbors).

Let's pretend that every single empty slot on the board will permit 4 moves. We know this is impossible in practice, because some slots on the board don't even have 4 valid neighbors. But, this assumption will get us an upper bound.

The most number of moves you could have at once, with this assumption, is when there are 7 empty spaces, or 28 (). The reason 7 empty spaces is the maximum is that once you reach 8 empty spaces, you become limited by the number of pegs left on the board.

So, if the most number of neighbors a node could have is 28, how many edges would we have if every node had 28 neighbors? Well, that's . Thus, the absolute maximum number of edges in this graph is less than a million. We could continue with a more sophisticated analysis but this worst-case upper bound is already low enough that there's no point.

Further Shrinking the Graph

The napkin math from the last section already shows the graph is small enough to process. However, we can exploit the symmetry of the game board to reduce the size of the graph even further.

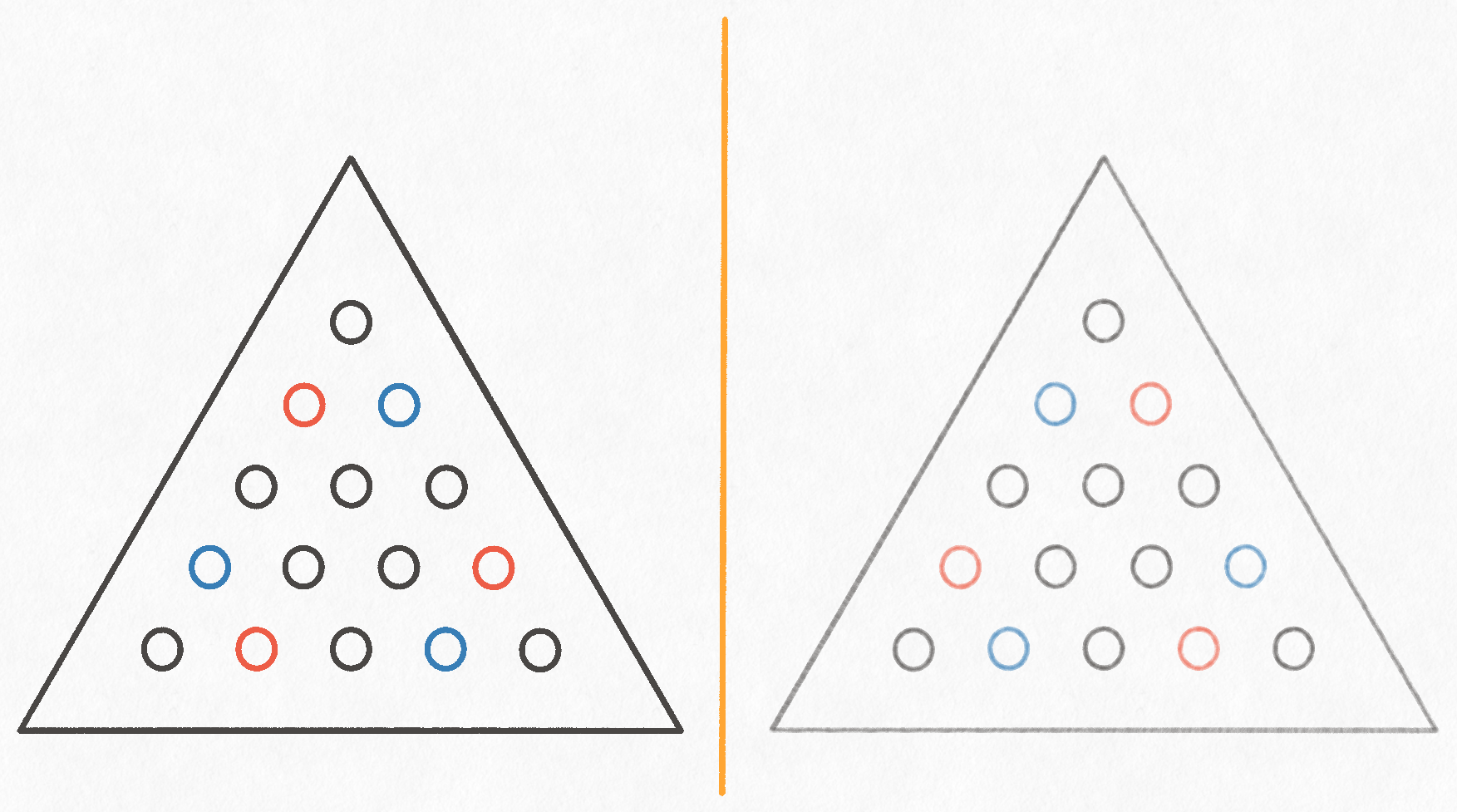

The Cracker Barrel version of the game doesn't stipulate the starting state of the board, other than requiring exactly one slot be empty. This means there are 15 different starting states. At first glance, it seems like it would be necessary to explore the game graph from each of these 15 options, but that's not the case!

There are actually only 4 unique starting points, with all other cells on the board being equivalent by symmetry. We can discount starting positions that are symmetrical because operations like rotating or mirroring the board don't change how the game pieces relate to each other, and therefore do not change the game. Choosing between different starting slots that are symmetrical to each other is only a "cosmetic" choice.

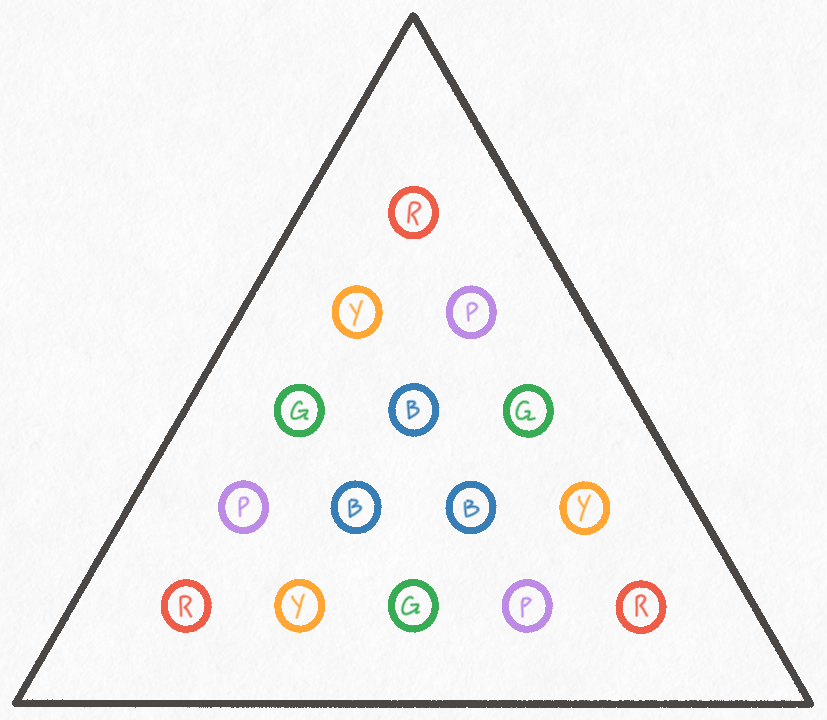

This is a situation where a picture is worth a thousand words, so I'm going to start with a diagram and then explain things in detail. Slots with the same color/letter are symmetrical and therefore equivalent starting positions.

This is most clear for the corners of the board. No matter what corner you choose, the board can be rotated so that it appears as if you chosen the top corner. Suppose you chose the bottom left corner to start and I chose the bottom right corner. No matter what move you played, I could simply rotate my board to match yours, copy your move, and then rotate my board back.

There's no need to explore the game from all three corners when the only difference between them is cosmetic.

This exact same argument can be applied to the 3 slots in the center of the board, as well as the slots in the middle of each edge.

This leaves a sort of "ring" of slots that are neither on the corners or the middle. I've labeled these slots "Y" and "P". The same rotational symmetry argument can be applied to these slots too, but an additional observation shows that the "Y" and "P" starting positions are equivalent to each other. Suppose we picked the slot to the bottom left of the top corner. If we held the board up to a mirror, it would appear like we chose the slot to the bottom-right of the corner. Reflection is another transformation, just like rotation, that changes how the board looks without changing the nature of the game.

This additional symmetry means we only need to explore the game from a "Y" slot or a "P" slot, but not both. Our final unique starting positions are as follows:

- One corner slot

- One center slot

- One slot on the middle of an edge

- One slot to the bottom-left OR bottom-right of a corner

Next Steps

Now that we have a model, we can move into writing some software!